Next-Level Security, Sensing, and Autonomy in Radar Technology

AIVO recently caught up with David Hunt, PhD candidate at Duke University. David works with the NSF AI Institute for Edge Computing Leveraging Next-generation Networks (Athena). This NSF-funded AI Institute’s goal is to transform the design, operation, and services of future mobile devices and networked systems.

We talked about his work with Athena on radar-based autonomy, a perfect fit with the Institute’s goal. Here’s the excerpt from our interview:

AIVO: What prompted you to delve into your current research area(s)?

David: Generally speaking, I have always enjoyed pushing the envelope and learning more about new technologies, especially looking at their practical applications.

Some things that motivated me: Both of my grandparents were engineers. And then there’s my previous work experience – I had the opportunity to work with Northrop Grumman and Raytheon in their space-based communications and radar-based areas. I got a bit of an understanding of some interesting research that was going on there, and some of the interesting things with the field going on there. In looking toward that, I said, I don’t want to just be building these things.

I want to be able to design systems, to design real-world things that can have an impact. I’ll get into my research a little bit later, but I would say my motivation is the general goal of pushing the envelope forward, wanting to be exploring, being very curious, and also having a big focus on systems, real-world implications, and making things that can better people’s lives.

AIVO: Can you give us some details about your research?

David: If you look at my research overall, the unifying theme is radar. Radar essentially is a sensor that uses radio waves to sense the environment around you.

You actually interact with radar a lot in your daily life. For instance, if you’re at the airport you can see the big spinny dish on top of the air traffic control tower that’s tracking planes. Radar is used on a boat or even in your car. If you’ve used an adaptive cruise control system that can start and stop with the car in front of you, or a blind-spot monitoring system, all of those use different variations of radar.

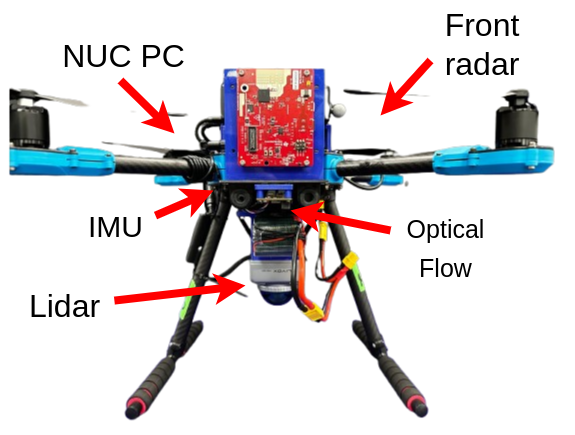

My specific focus with radar deals with millimeter wave radar, which is the latest generation. It’s at a bit higher frequency, specifically about 77 GHz. Being at that high frequency allows us to shrink those radars down quite a bit. The radars that I work with are the ones that are in your cars, the ones for forward collision warning or adaptive cruise control or blind-spot monitoring. So that’s the common theme of my research: What can we do with radar?

So what are some of the questions and some of the areas that I study? I would break it down into a few things.

- The first is, we look at the security of these sensors. We don’t want somebody being able to add a car and make your car think that there’s something in front of it when there’s not. We also want to make sure that nobody can remove a car or make you fail to detect something.

- We also look at how we can use radar to sense the environment around us, especially in the area of autonomy. I’ll use an example to explain what I mean here.

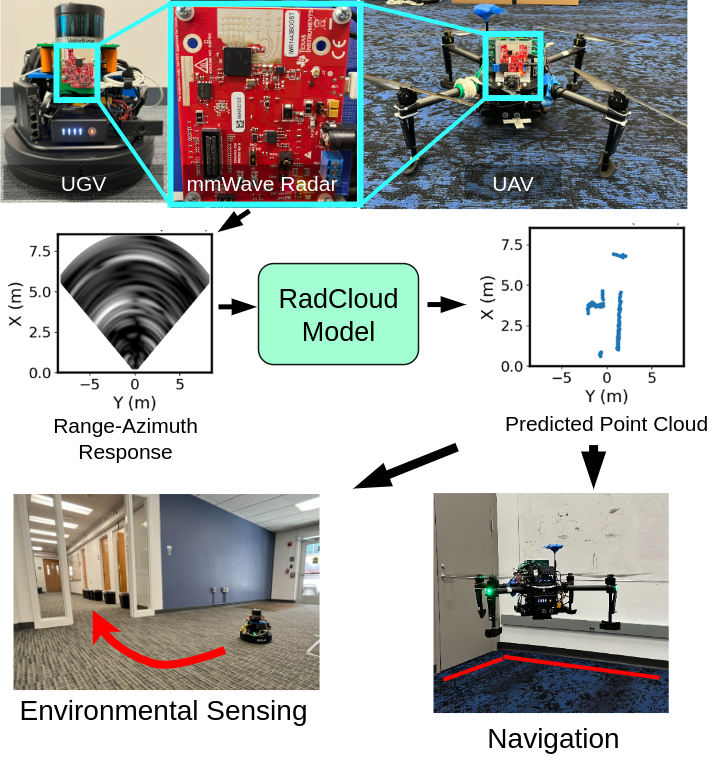

Most everybody has a Roomba in their house, or people are at least familiar with a Roomba, the autonomous vacuum. When it started out, it would just bounce around your home trying to bounce into everything – not very intelligent. And now you’re starting to see some being able to map. What we’re looking at is, can we put this very cheap and affordable sensor on different devices, like a ground vehicle or even a drone?

That begs more questions, basically looking at what we can do with radar:

Can we use that affordable sensor to sense the environment around us, so we can avoid obstacles?

Can we also use that sensing to determine our location in a room, or create a map of the environment?

Can we use it to autonomously navigate through a specific space? We look at that not only in the context of ground vehicles, but also drones.

How can we deploy an affordable sensor on robot dogs? - The other area that I also look at is in contested environments, where resilience is key. We’re seeing cases with Ukraine, for instance, which is a big conflict area. What we’re finding is, drones play a big impact. But when we look at those drones, adversaries are now jamming both the GPS and communications that are used to estimate location and communicate with drone operators. So, we are looking at how we can use radar to make drones resilient.

I’ve said a lot about radar and how we’re using it. But the important thing is, why are we using it? That’s another thing that might be helpful to understand here. If we ask the question of “why radar,” there are a few reasons that might be helpful to give further context.

It’s worth comparing radar to other sensors. There are other ways that we can sense our environment, like the cameras you have on your smartphone. You also have lidar (light detection and ranging), which basically shoots a laser out. It’s spinning very quickly, and it gives you a very dense, rich, point cloud of your environment.

But when we look at those sensors, we see that there are some reasons that they don’t work as well in certain environments. For instance, a camera works great in a well-lit environment with lots of features. If you’re in an environment that’s really dark, smoky, or foggy, like one you might find in an emergency response situation, like fighting a fire, a camera doesn’t work as well.

And likewise with lidars. They’re very accurate, but traditionally they’re quite expensive, and you may not need that high of a resolution (of a point cloud) for certain applications. And they can also be susceptible to environmental things like smoke or fog.

By contrast, the radars that I work with are actually quite affordable. Even a development board is about $200. But for the specific chip on there, that you can buy for $20 or $30. So it’s fairly affordable.

Radar provides really accurate ranging even in poor weather or lighting conditions, or anything like that, and it can also uniquely sense the velocity. We can really easily detect moving objects like people in the environment, for instance.

Radar is also very lightweight. It doesn’t require too much processing in our case. But there are some challenges that we have to overcome. For instance, these radars are very low, angular resolution. Whereas cameras and lidars have very high angular resolution, we have very poor resolution. So we’re looking at how we deploy AI or just advanced radar signal processing algorithms to improve that, to be able to leverage them in the kind of applications that I talked about earlier.

Hopefully that explanation gives a bit better understanding of some of the research that I do!

AIVO: What is the goal of your project and/or its practical or real-world use?

David: This is really a great question, especially in motivating my research. So let’s take that second question that I was focused on and look at autonomy. When we look at the practical, real-world concerns, there are a few things that we want to prioritize. We want something that’s affordable. You don’t want to spend $1,000 or $2,000 on your Roomba or on a robotic platform.

So there are cost constraints that we want to consider. When we enable autonomous platforms, there might be compute constraints. In the AI space these days, you hear a lot about GPUs (graphics processing units) and advanced and really powerful computers. These can be fantastic. But maybe we can’t mount that computer. Or maybe your platform doesn’t have that capacity. Maybe you have an $80 computer which has very limited computation.

There are size constraints, or compute constraints. And then there also can be power or other types of constraints that have to be considered. The reason I bring those up in answering your question is when we look at practical systems, they have constraints. They have limitations, and you have to work within that budget. You know those constraints when you build a platform.

In my research, what we’re looking at is how we can use these affordable, small, lightweight sensors on real-world platforms to make them autonomous – even in a resilient environment where an adversary may be trying to jam you or when the environment is not ideal.

How can we then leverage advanced algorithms and AI and all of these different advanced techniques to effectively get great or good enough sensing on our platform to enable key tasks for autonomy – like determining your location, generating a map of the environment, tracking, moving obstacles, and then ultimately performing autonomous navigation from there? One of the really interesting things that we look at is, how do we scale the processing and the computational requirements to meet a certain application?

Just to give you an example, let’s take two cases.

- Let’s take the case of the Roomba, something that a lot of people deal with.

I don’t really need a high-fidelity map of my house. I might want to know where the couch is, and I need to know where the walls are, so that I don’t collide, but I don’t need to know it down to the centimeter. I certainly don’t need to know all the intricacies of the chair legs and stuff. I can navigate through a rough course map. So maybe I can use a very simple model, like one that we developed with graph neural networks to generate a good enough map and sensing to perform that task, but on a reduced computational capability or on a very resource-constrained computer. - On the other hand, maybe we have something where we want to do a bit higher resolution sensing. Maybe we’re exploring a cave. Or we want to actually see full objects and get a high-resolution map.

There we can scale up our processing by doing some advanced radar signal processing. Then combining that with AI and advanced models, you run an advanced model on our platform and develop and perform higher resolution sensing of the environment. We can scale and adapt based on a platform’s needs. And that’s really important, especially when we look at real-world platforms that will operate in real-world environments and have real constraints.

Hopefully, that helps give an idea of some of the reasons for the goals that we have, as well as some of the real, practical elements.

AIVO: What’s the role of Athena in your project?

David: For those that aren’t familiar with it, Athena is a multi-institutional collaboration. To name a few of the schools, there’s Duke, Michigan, Yale, and Wisconsin. We’re all coming together, and we’re working on edge AI. So how do we deploy AI on advanced or edge devices? For instance, for that super-constrained platform, how can we use edge computation? Maybe we have a powerful computer located within the same building. But it’s not running on the actual device.

And how can we use the edge to deploy AI on small resources, constrained devices, or just generally? And also one of the big areas that Athena is working on is, how can we work with a bunch of different platforms to give a better explanation?

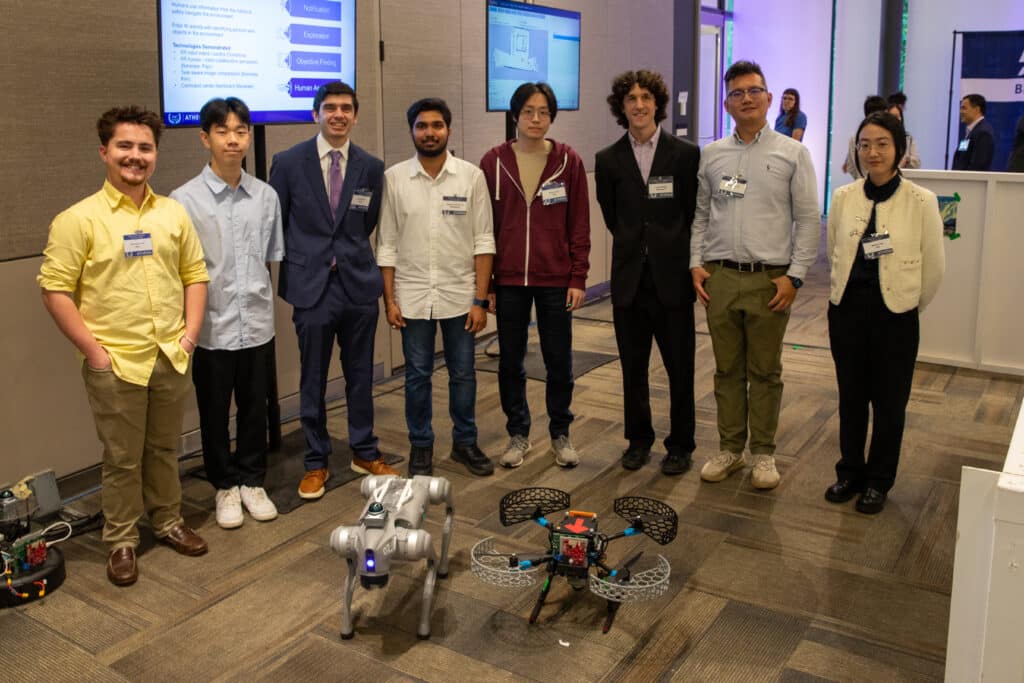

I’ll talk a little bit about a recent demo and highlight some of the things that Athena is doing.

So let’s take an emergency response. There are firefighters arriving at the scene of an emergency. Maybe they have a rough map, but they don’t have a full-scale map.

So we’re going to send some autonomous robots into the environment. Some of my work gets deployed where we’re sending in robots with radar, or maybe lidar and camera to sense the environment.

Now, one of the first things that Athena is helping to enable is collaborative sensing and situational awareness. We don’t want to just send one robot in there, and it only has its local sensing performed. We can actually go in and combine sensing across multiple agents, through the power of the research that Athena is doing. We can combine the mapping and sensing, for instance, from a drone. Maybe the right drones can’t open doors, so we send in a robot dog with a similar sensing suite, and then we can. We can have those talking to each other, and in addition to talking to each other, they can share their sensing and mapping to an edge server, which is also connected to the first responders in a command center, for instance. There’s that situational awareness in being able to share information.

Another really cool thing that we’ve been able to do with Athena is leverage unique interfaces. For instance, XR (extended reality), which is a combination of VR (virtual reality) or AR (augmented reality). Many people have heard of the Apple Vision Pro, the Meta Quest, popular headsets, or augmented reality where you used the Microsoft Hololens, for instance. It’s a really cool thing to take these headsets as a new way of interacting and controlling different platforms.

Say, for instance, instead of having to work on your laptop to control the robot, you wanted to point to where it is in real space. With Athena and the collaborations that we’ve been able to do, I could be wearing goggles, glasses, or a VR headset, and it’ll show my entire environment. I can point to a location and the robot dog will autonomously navigate there.

Additionally, because we have that collaborative sensing, now we can send first responders in, and they can have a map. They can pull up their hand and see a map that was generated from other robots. At the same time we can put up a plot, or localize them in the scene, so they can see a preferred route or an optimized route that they should take.

With that kind of work with new interfaces like XR, AR, and VR headsets, we can do collaborative sensing. And we can also deploy advanced AI.

This isn’t my direct research, but we can use also large language models (LLMs) to control robots. An area where my research is coming into play with Athena now is path planning and coordination of multiple robots.

We can use ChatGPT or language models and feed in maps that are generated from different robots. We’re able to have them collaboratively sense the environment and find ideal ways. We consider how to use edge computing to collaboratively sense environments or share measurements, how we have novel interfaces, and how we can deploy advanced AI that we would never be able to deploy on a very resource-constrained platform. But through the power of edge computing, we’re able to perform those tasks.

AIVO: It sounds like you have a ton of use cases!

David: It’s been really interesting, because as I mentioned earlier, my main research is radar-based autonomy. That’s one of my main areas. And now what I get to do is figure out a novel interface. Can we do an AR headset? How can we incorporate something new?

For example, Yale has a project called Typefly, where you can do LLM-based control of a UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle). We can deploy that with our drones and ground vehicles that are radar-equipped. And likewise with all of these other people that have different interfaces, platforms, or methods of coordination. We can plug our platform right in there. So it’s this really powerful collaboration and integration of so many different technologies that, in my opinion, any single institution wouldn’t have been able to create on their own. But together we’re able to really showcase the power of edge computation, Edge AI, advanced algorithms, sensing, and whatnot.

AIVO: How do you work with their team to move your project forward?

David: The best way to look at this is probably in kinds of tiers. On the personal level, I do my primary research on my specific projects. But I’m always keeping in the back of my head, how can we integrate this with Athena? Or how might this fit with the Athena Institute?

One of the great ways that this collaboration has been motivated, and has happened not only in collaborations through papers and whatnot, is that we do demos. Through those demos I get the opportunity to see what all of the other institutions are doing, but then also be able to talk with them about how we can find common platforms or ways of connecting with each other’s research. And we put on larger demos and put together larger work, where we’re able to all talk with each other.

I’ve had weekly meetings with the team for quite a while now where we’re saying, how do we integrate this? How do we integrate LLM-based drone control with a new platform? Or how do I integrate my sensing, mapping, and navigation algorithms with a command center that say Wisconsin has designed?

It’s this inter-university teaming that we’re able to do through Athena. It’s not just at the faculty level, but as students and postdocs where we can talk to people that are doing all this research and see how we can combine everything together. We have great faculty mentors and a great leadership team, and they’re looking at it all from an even higher level perspective and saying, here’s where we need to promote that collaboration.

There are the main areas that we want to target – working from my individual research to working with multi-university teams of students and faculty, and also getting that feedback from the faculty and the Athena staff and mentorship team. This really promotes that collaboration and allows us to do – as hopefully I’ve shown – some really great work!

AIVO: How did you find out about the opportunity to have a project with Athena?

David: Duke is one of the main institutions in Athena. In my lab, with my advisor, we are one of the leads for the situational awareness pillar, which is one of the the core pillars of Athena. The opportunity was through that role and in hearing about all the different things Athena wanted to do. And also just by the nature of the research that I’m doing, it ended up being a natural collaboration. I’m very grateful for the opportunity, because it’s allowed me to extend my research in a way that I never would have been able to.

AIVO: Wonderful! It sounds like you have a very healthy working environment there.

David: I will plug Duke a little bit! We have a great environment, a great culture. Athena as well – it’s a very collaborative institution. I’m glad for that. And for the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF).

Thank you to NSF. NSF is the main funder of Athena.

We’re very lucky that we have this Institute. Hopefully, it’s showing, because of all the different collaborations and ways that we can interact with people from other schools in a way that you really wouldn’t have been able to previously. So it’s very, very exciting!

AIVO: You’re studying electrical and computing engineering. What are some ways you plan to use your PhD after you graduate?

David: Recently, I was awarded the Department of Defense (DOD) SMART Fellowship, which will allow me to work with the Department of Defense. I’ll be with Navy research labs moving forward after I graduate! I’m really excited to see how I can take some of the lessons that I’ve learned and put them into mission-critical or safety-critical applications.

But even more than that, as I close out my PhD, which I’ve still got two years left, so not going anywhere anytime soon, I’m really excited to enter the working world. I’m really excited to design systems and technologies that are practical and have real-world implications and operating constraints.

I’ve been able to look at and understand a lot when it comes to autonomy and various sensors, not just radar. But I’ve also interacted with lidar and camera based-techniques, as well as different platforms from ground vehicles to drones to aerial vehicles. So I’m looking to take all of the knowledge that I’ve gained and be able to deploy it in real world-scenarios – not only just in defense, but even in emergency response – or even I suppose, in developing a better vacuum.

AIVO: Is there anything you’d like to add that we haven’t covered in the interview yet?

David: I haven’t talked too much about how we really want to collaborate. We also want to motivate students to be a part of it, whether it be my lab or Athena and the great work that we are doing.

In addition to the opportunities to contribute to the research and the ultimate goals, I’ve also had the opportunity to mentor high school students, to put on kids camps, and to mentor undergraduate students as well. I would encourage people out there that are students at Athena schools, or even if you’re not at one of the Athena institutions but you want to do a summer research program.

There’s certainly a lot of room for people to get involved. We design things within academia, and if there are outside collaborators in industry, we want to learn from them and understand what the real-world cases are.

I would really encourage people to connect to get involved. If there is any way, whether it be in direct research or in helping out. The Athena Institute is really exciting, even beyond what we do here at Duke. I’m happy to connect, happy to collaborate with people and encourage people to get involved in any way that they may be interested to do!

AIVO: Thank you! That’s always a timely message to give back.

David: I think it’s really important. And for all the future engineers out there, there are lots of ways that you can get involved. You don’t have to get a PhD to get involved. You could do a summer research opportunity, or even just learn about some of these technologies that are coming to your lives soon. Know how to use them, how to design them, how to leverage them.

And we’re always excited to collaborate, not only to mentor students, but also to collaborate with industry and academia alike.

Thank you so much to David for talking with us and sharing your insights! We’re thrilled to learn about your accomplishments and wish you continued success in your career!

Learn more about David’s work

- Athena Tech Showcase ‘25 presentation – “Resource-Constrained Intelligence for Radar-Based Autonomy” – David Hunt and Miroslav Pajic

- RaGNNarok (IROS ’25 submitted): A lightweight graph neural network enabling efficient radar point cloud enhancement to enable localization, navigation, and mapping on resource constrained unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs).

ABOUT ATHENA

Athena focuses on developing edge computing with groundbreaking AI functionality that leverages next-generation communications networks to provide previously impossible services at reasonable cost. Based at Duke University, the Institute brings together a multidisciplinary team of scientists, engineers, statisticians, legal scholars, and psychologists from seven more universities:

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University

- Princeton University

- Purdue University

- University of Michigan

- University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Yale University